Evidence at the Court of Tax Appeals

Tax appeals are filed before the CTA

The Court of Tax Appeals is a special court to which either the taxpayer or the government may elevate tax controversies.

Because it is a court of law, the CTA’s decisions must be based on evidence presented to it.

This article discusses various considerations with respect to evidence at the CTA.

Contents

- The standard of proof at the Court of Tax Appeals

- What rules of evidence govern at the Court of Tax Appeals?

- How do you present evidence at the Court of Tax Appeals?

- The Judicial Affidavit Rule

- What kinds of documentary evidence are necessary?

- The Rules on Electronic Evidence

- Trial de novo

- Independent CPA’s Report

- Formal Offer of Evidence

- Appealing a CTA decision to the Supreme Court

The standard of proof at the Court of Tax Appeals

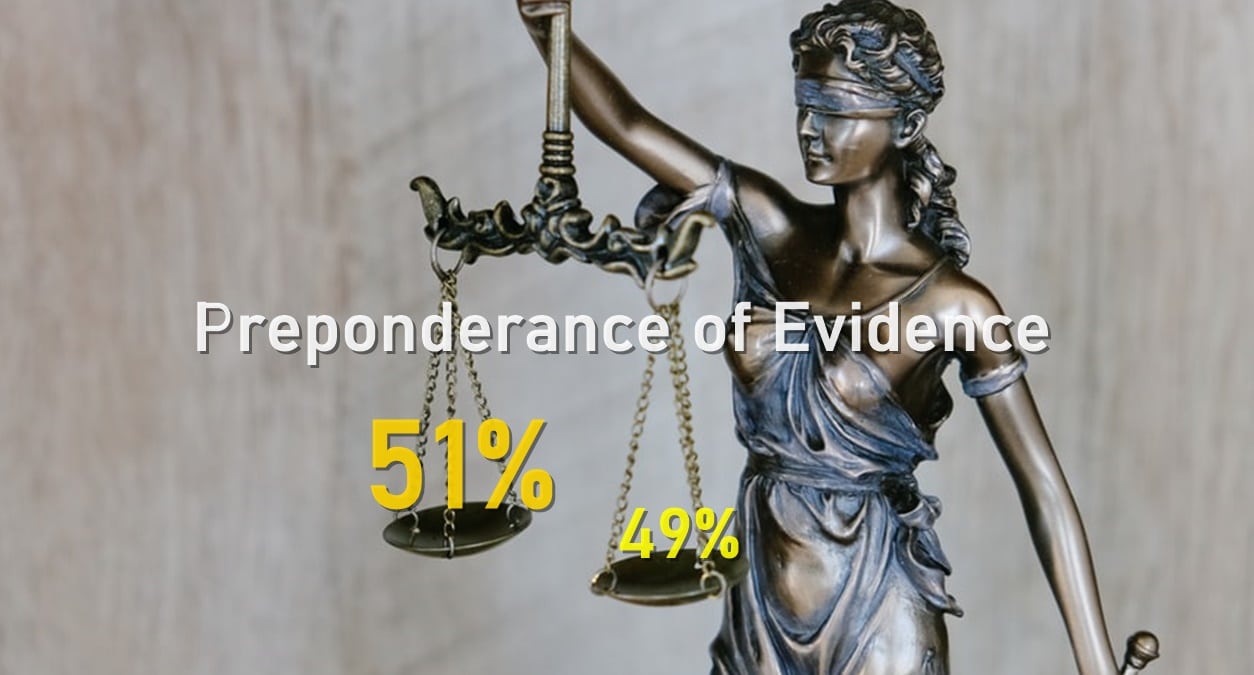

“Preponderance of the evidence” is the standard of evidence.

The CTA decides both civil cases (such as those for tax refunds) and criminal cases such as tax evasion.

In a civil case, it is the taxpayer’s burden to prove that the decision or inaction of the taxing authority was wrong and should be overturned. The taxpayer must establish his case by a preponderance of evidence, which means evidence of greater weight, or more convincing than that offered in opposition to it. At bottom, it means probability of truth.[1]

Criminal cases impose a greater burden of proof from the prosecution. The prosecution must prove guilt beyond reasonable doubt. This is proof sufficient to produce moral certainty that would convince and satisfy the conscience. Proof beyond reasonable doubt requires enough evidence to produce conviction in an unprejudiced mind and overcome the constitutional presumption of innocence.[2]

Beyond a reasonable doubt is the standard of proof required for a criminal conviction

Two things must be established beyond reasonable doubt in criminal cases: first, all the elements of the crime charged; and second, that it was committed by the accused.

After either the petitioner (in civil cases) or the prosecution (in criminal cases) rests its case, the respondent or the accused may choose to file a demurrer to evidence. A demurrer is an objection by one of the parties in which he argues that the case against him should be dismissed for failure to present enough evidence to discharge the burden of proof. If the demurrer is granted, the party need not submit any evidence of his own.

[1] Benedicto v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, CTA Case No. 6847, April 2, 2009.

[2] People v. Cando, CTA Crim. Case No. O-634, September 11, 2019.

What rules of evidence govern at the Court of Tax Appeals?

The CTA is not strictly governed by the rules on evidence.

The law creating the CTA expressly provides that it is not strictly governed by the technical rules of evidence.[1] The CTA thus has latitude on what evidence it will admit and how it will appreciate it, the paramount consideration being the ascertainment of truth.[2]

Having said that, it remains a court of law and a court of record. As such, the CTA still routinely applies the rules of evidence in deciding whether to admit particular exhibits and how much weight to give them.

These rules are found in the Rules of Court, the Revised Rules of the Court of Tax Appeals, the Rules on Electronic Evidence, the Judicial Affidavit Rule, Supreme Court and CTA jurisprudence, and other issuances of the courts.

[1] Republic Act No. 1125

[2] People v. Cross Country Oil & Petroleum Corp., CTA Crim. Case No. 0-631, March 13, 2018 citing Philippine Phosphate Fertilizer Corporation v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, G.R. No. 141973, June 28, 2005]

How do you present evidence at the Court of Tax Appeals?

The CTA also has videoconference hearings as a COVID related measure.

Testimonial, object, and documentary evidence are presented to the CTA during the trial.

The testimony of witnesses is required to identify and explain documents so that they may be admitted into evidence. Because the CTA is a court of record, the evidence must have been duly identified by testimony and this evidence must be put on the record for it to be considered.

The Judicial Affidavit Rule

The Judicial Affidavit Rule makes the process easier and is more practical.

The Judicial Affidavit Rule, which governs the presentation of witness testimony in court cases, applies at the Court of Tax Appeals. The purpose of the JAR is to reduce the time needed to receive witness testimony.[1]

Prior to trial, a witness’s testimony must be put into writing as a sworn affidavit in question and answer format, with counsel asking the questions and the witness answering. Copies of exhibits and evidence which the witness identifies in the affidavit must be attached to it.

The written judicial affidavit takes the place of the witness’s direct testimony in open court. When the witness is called to testify on the day of the hearing, he or she will simply identify the affidavit and affirm its contents in court. This does away with lengthy and tedious direct examination of the witness at the hearing, saving the court’s time, and allowing the witness to immediately be cross-examined.

There is a 30 day window to appeal a decision or inaction of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to the CTA.

The Rules require that the judicial affidavit be submitted well before the court hearing date. The judicial affidavit and the copies of the evidence should be filed with the CTA at the same time as the Petition for Review itself.[2]

The 30-day window to appeal a decision or inaction of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to the CTA is thus a busy time. The taxpayer’s counsel, who was often not yet involved at the administrative level, must draft not only the Petition for Review within this window but the witnesses’ judicial affidavits as well. Counsel must also as obtain and organize the evidence he intends to present at the CTA within this time.

[1] A.M. No. 12-8-8-SC.

[2] CTA En Banc Resolution No. 9-2020.

What kinds of documentary evidence are necessary?

Documentary evidence must be original

Any evidence relevant to a claim or charge may be presented to the CTA. Original and corroborated documents are given preference in terms of evidentiary value. These include corporate and accounting records, sales invoices, receipts, vouchers, export declarations, bills of lading or airway bills, bank credit advisories, certificates of bank remittance, certifications by government agencies (such as the SEC, Central Bank, Bureau of Customs, PEZA, etc.) of relevant facts, and others.

The CTA constantly invokes the formal rules when ruling on whether to admit exhibits submitted to it as evidence.

In Sumisetsu v. CIR,[1] the CTA denied an input VAT refund claim because of the taxpayer’s failure to comply with the exacting rules of Evidence on how a public document should be proved in court.

The CTA prefers originals

The CTA refused to consider a certified true copy of a Clark Freeport Zone certification that sales to an entity were zero-rated, ruling that the certification was by a person whose authority to do so was unknown. This was because the taxpayer’s failure to the certifier’s authority is required by Sections 19 and 24, Rule 132 of the Rules of Court.

In the same case, the CTA reiterated the rule of evidence that the originals of documents should be presented to it or else they would be rejected by the court. And, even when mere photocopies are accepted by the CTA, they were accorded no probative value because their genuineness and authenticity could not be ascertained under the rules of evidence.[2]

Foreign public documents must be duly authenticated to be admissible in evidence. For most treaty members of the Hague Apostille Convention, this authentication is a certification on the document in the form of an apostille issued by the competent authority designated by each country.

[1] CTA Case No. 8062, August 13, 2015.

[2] Sumisetu v. CIR, supra.

The Rules on Electronic Evidence

The CTA may also admit evidence in their digital form.

The exacting Rules on Electronic Evidence are also regularly referred to by the CTA, both in judging whether to admit an electronic document or print out submitted by a party and in determining how much weight to give such a piece of evidence.[1]

[1] AM 01-7-01-SC.

Trial de novo

The expression trial de novo means a “new trial” by a different tribunal

Appeals before the CTA are tried de novo, anew. For this reason, the Court has rejected the government’s argument that, in a case to determine a taxpayer’s entitlement to refund, it should only consider documents that were previously submitted at the administrative level.

The non-submission of complete supporting documents at the administrative level is not fatal to the taxpayer’s judicial claim. The CTA is not barred from receiving, evaluating, and appreciating new evidence submitted to it. Once the claim for refund has been elevated to the Court, the admissibility, materiality, relevance, probative value, and weight of evidence presented become subject to the relevant provisions of the Rules of Court. It is up to the CTA to resolve whether the evidence submitted to it warrants granting a claim for refund.[1]

A taxpayer’s claims at the CTA should not be denied on the sole ground that the taxpayer allegedly failed to submit before the BIR the complete documents in support of its administrative claim for refund. Judicial claims are litigated de novo and decided based on what has been presented and formally offered by the parties during the trial.

EDC Burgos Wind Power Corporation (EBWPC), a subsidiary of EDC, is the owner and operator of the 150-MW Burgos Wind Project in Burgos, Ilocos Norte.

However, this is not a license for a taxpayer to disregard (or fail to address) what transpired at the administrative level.

In EDC Burgos Wind Power Corporation v. CIR,[2] the CTA ruled that since it is an appellate court, it is imperative for the taxpayer to show not only that is he entitled under substantive law to his claim for refund or tax credit, but also that he satisfied all the documentary and evidentiary requirements for an administrative claim with the BIR. It is crucial for a taxpayer in a judicial claim for a refund or tax credit to show that its administrative claim should have been granted in the first place.

The CTA found that EDC Burgos Wind Power Corp. failed to do this because it had presented its case as if its administrative claim had never been acted upon or that there was no decision for the Court to review on appeal. The company had presented its CTA case as if it was an original action, despite the BIR having explicitly denied its administrative claim.

The BIR denied the claim of EDC Burgos Wind Power Corporation for a tax refund

The BIR had made a finding that no zero-rated sales were made during the taxable quarter, and therefore there was no creditable input tax attributable to such zero-rated sales.

When it elevated the case to the CTA, the company did not specifically contest the reason or basis why its administrative claim was denied in the first place. It never argued or proved that the said reason or basis was not justified in law.

The company should have specifically argued and proven that these findings of zero-rated sales during the period were erroneous and had no leg to stand on. The CTA ruled that the company had failed to do this and denied the company’s appeal.

The CTA draws a distinction between cases appealed to it due to inaction by the taxing authority and those which were dismissed at the administrative level due to the failure of the taxpayer to submit supporting documents.

The CTA also recognizes the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies.

If an administrative claim was dismissed by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue due to the taxpayer’s failure to submit complete documents despite notice, then the appeal claim before the CTA would be dismissible because of the taxpayer’s failure to substantiate the claim at the administrative level.

When appealing to the CTA, the taxpayer must convince the Court that the CIR had no sound reason to deny its claim. It is imperative for the taxpayer to show not only that is he entitled under substantive law to his claim for refund or tax credit, but also that he satisfied all the documentary and evidentiary requirements for an administrative claim.

It is crucial for a taxpayer in a judicial claim for a refund or tax credit to show that its administrative claim should have been granted in the first place. Consequently, a taxpayer cannot cure the failure to submit a document requested by the BIR at the administrative level by filing the said document before the CTA.

In case of inaction, the CTA may then give credence to all evidence presented by respondent.

Things are different if inaction on a claim was the reason for appealing to the CTA. For example, if the CIR did not send any written notice informing the taxpayer that the documents it submitted were incomplete, or did not require the respondent to submit additional documents, or did not even render a Decision denying the claim on the ground that it had failed to submit all the required documents.

Consequently, the CTA may then give credence to all evidence presented by the respondent, including those that may not have been submitted to the CIR since the case is being essentially decided in the first instance.[3]

[1] CIR v. Chevron Holding, Inc. / Chevron Holdings, Inc. v. CIR, CTA EB Nos. 1886 and 1887 (CTA Case No. 9021), January 21, 2020.

[2] Case 9446, March 12, 2021.

[3] CIR v. Univation Motor Philippines, Inc. G.R. No. 231581, April 10, 2019 citing Pilipinas Total Gas, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 774 Phil. 473 (2015).

Independent CPA’s Report

Certified Public Accountant, is a trusted financial advisor who helps individuals, businesses, and other organizations plan and reach their financial goals.

In the course of the trial, the CTA may commission an independent Certified Public Accountant as an officer of the Court for the purpose of performing audit functions. The ICPA’s duties include the examination of voluminous documents and the submission of a formal report with certification of authenticity and veracity of findings and conclusions in the performance of the audit.

The evidence on which the ICPA’s report is based should itself be submitted to the CTA. Documents referenced in the ICPA report, even those already determined by the ICPA to be either original copies or faithful reproductions of the originals, should be offered to the CTA, or else they may not be admitted into evidence.

Submissions to the CTA should be originals

Original receipts, invoices, vouchers, or other documents which were examined and marked by the Court-commissioned Independent Certified Public Accountant Exhibits should be presented to the CTA and formally offered into evidence.

The CTA has refused to admit into evidence mere photocopies of such documents on which the ICPA report was based in cases where the taxpayer failed to explain why the originals could not be presented.[1]

[1] AIG Shared Services Corp. v. CIR, CTA Case Nos. 86`5 & 8647, January 29, 2019.

Formal Offer of Evidence

Before any documentary evidence is admitted, appellants must first file a formal offer which itemized the exhibits

Evidence presented must be formally offered. In a formal offer, the evidence is listed and the purposes for which each is offered are explained. A formal offer is necessary because the Rules bind judges to base their findings of facts and judgment only upon the evidence offered by the parties at the trial. Evidence not formally offered is deemed to be without any weight or value.[1]

As cases filed with the CTA are litigated de novo, party-litigants must prove every minute aspect of their cases. Therefore, no evidentiary value can be given to pieces of evidence which were not formally offered before the CTA.

The offer into evidence must be formal and explicit. Even if a particular document was identified and marked as an exhibit, this does not mean it has already been offered as part of the evidence of a party. Although the CTA is not governed strictly by technical rules of evidence, the presentation and formal offer of the evidence is not a mere procedural technicality that may be disregarded since it is the only means by which the CTA may ascertain and verify the truth of the party’s claims. Failure to formally offer evidence is fatal to a party’s cause.

[1] Prudential Life Plans, Inc. v. CIR, CTA EB Case No. 1219, April 19, 2016.

Appealing a CTA decision to the Supreme Court

If an appeal is still unfavorable, appellant can elevate it to the higher court.

The CTA’s appreciation of the evidence it received in the trial is usually determinative even when appealed to the highest court.

A decision of the Court of Tax Appeals may be appealed to the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court accords the utmost respect to the CTA’s findings of fact as a highly specialized body constituted to review tax cases. For this reason, the CTA’s findings of fact are deemed binding on the Supreme Court unless they are not supported by substantial evidence.[1]

Atty. Francesco C. Britanico

[1] Barcelon, Roxas Securities, Inc. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, G.R. No. 157064, August 7, 2006.

0 Comments