Lessee’s right of renewal clauses in lease agreements

Renewal of Philippine Lease Agreements

Is the lessee’s Right of Renewal of Philippine lease agreements void due to the Civil Code statement that a condition is void if its fulfillment depends upon the sole will of the debtor?[i]

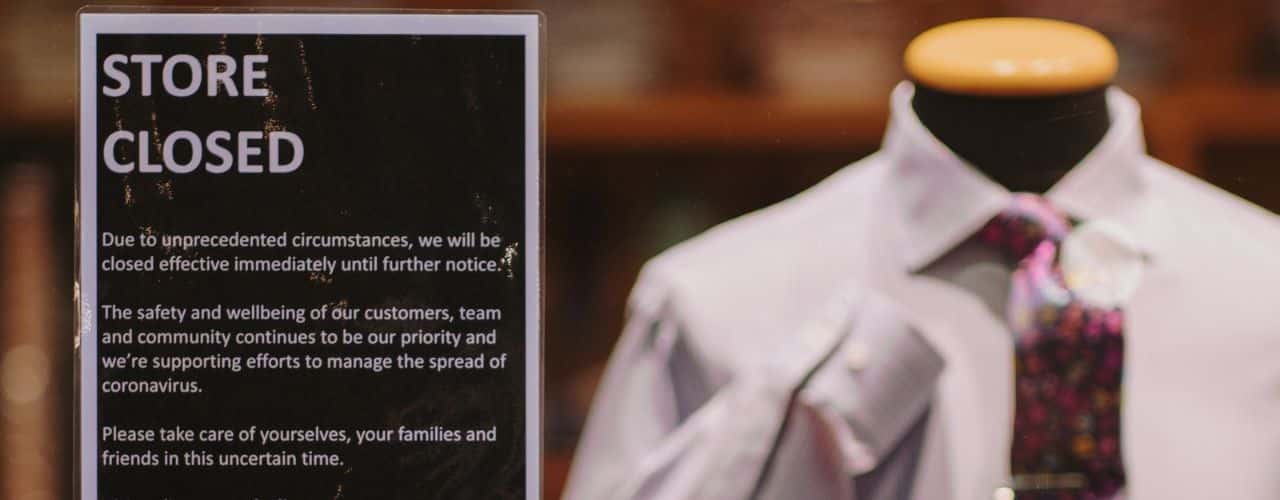

Renewal of an existing lease agreement is a contract to have new one often when the original contract expires, not because it is a requirement of the business relationship.

If a provision in a lease contract unilaterally allows the lessee to renew the lease under the same terms, isn’t that a void clause?

This article discusses the lessee’s Right of Renewal for Philippine lease agreements and associated jurisprudence.

Potestative Conditions and the Right of Renewal of Philippine Lease Agreements

Leases are mostly drafted disparately but have some standard features.

Some have argued that unilateral right of renewal clauses are invalid for being potestative, and therefore void, conditions.

A potestative condition is an invalid condition because it depends solely on the will of one of the parties.

However, the Supreme Court has rejected this argument and has consistently upheld the right of renewal clauses.

Let’s take a look at some important jurisprudence with regard to the Renewals of Philippine Lease Agreements below.

Case 1: Allied Banking Corporation vs. Court of Appeals

The Supreme Court addressed such a controversy in Allied Banking Corporation vs. Court of Appeals.

There, the Supreme Court took up the issue of:

If you’re into extending your lease agreement concurring on the length of the next term along with any break clauses a renewal is needed.

whether a stipulation in a contract of a lease to the effect that the contract “may be renewed for a like term at the option of the lessee” is void for being potestative or violative of the principle of mutuality of contracts under Art. 1308 of the Civil Code and, contrarily, what is the meaning of the clause “may be renewed for a like term at the option of the lessee

The Supreme Court ruled that such a stipulation is not potestative and is therefore valid.

It also ruled that the clause “may be renewed for a like term at the option of the lessee,” which meant that the lessee’s exercise of the option resulted in the automatic extension of the contract of a lease under the same terms and conditions.

Case 2: Manila International Airport v. Ding Velayo Sports Center, Inc.

Allied Banking Corp. was later cited and affirmed in Manila International Airport v. Ding Velayo Sports Center, Inc.

Manila International Airport rejected the lessor’s argument that a provision for renewal in the Philippine lease agreement that depended solely on the choice of the lessee was a potestative condition.

Such a provision was determined to be valid.

Renewal of Philippine Lease Agreements can be a difficult process. We recommend you get professional help from adept lawyers around the area.

The Supreme Court ruled that:

Article 1308 of the Civil Code expresses what is known in law as the principle of mutuality of contracts. It provides that “the contract must bind both the contracting parties; its validity or compliance cannot be left to the will of one of them.” This binding effect of a contract on both parties is based on the principle that the obligations arising from contracts have the force of law between the contracting parties, and there must be mutuality between them based essentially on their equality under which it is repugnant to have one party bound by the contract while leaving the other free therefrom. The ultimate purpose is to render void a contract containing a condition that makes its fulfillment dependent solely upon the uncontrolled will of one of the contracting parties.

An express agreement that gives the lessee the sole option to renew the lease is frequent and subject to statutory restrictions, valid and binding on the parties. This option, which is provided in the same lease agreement, is fundamentally part of the consideration in the contract and is no different from any other provision of the lease carrying an undertaking on the part of the lessor to act conditioned on the performance by the lessee. It is a purely executory contract and at most confers a right to obtain a renewal if there is compliance with the conditions on which the right is made to depend. The right of renewal constitutes a part of the lessee’s interest in the land and forms a substantial and integral part of the agreement.

If you’re wondering how to extend a lease contract it’s always best to ask your lessor to have a clear validation of the arrangement.

The fact that such an option is binding only on the lessor and can be exercised only by the lessee does not render it void for lack of mutuality. After all, the lessor is free to give or not give the option to the lessee. And while the lessee has a right to elect whether to continue with the lease or not, once he exercises his option to continue and the lessor accepts, both parties are thereafter bound by the new lease agreement. Their rights and obligations become mutually fixed, and the lessee is entitled to retain possession of the property for the duration of the new lease, and the lessor may hold him liable for the rent therefor. The lessee cannot thereafter escape liability even if he should subsequently decide to abandon the premises. Mutuality obtains in such a contract and equality exists between the lessor and the lessee since they remain with the same faculties with respect to fulfillment.

Republic v. Philippine International Corporation

As a reminder agreement is subject to legal restrictions that must be valid and binding on the parties, so it’s best to communicate the details of it. In most cases, real state Lawyers can answer the question there and then.

More recently, in Republic v. Philippine International Corporation, the Supreme Court again upheld a ruling with respect to a contract provision giving a lessee the sole option to renew a lease, thus:

An express agreement that gives the lessee the sole option to renew the lease is frequent and[,] subject to statutory restrictions, valid and binding on the parties. This option, which is provided in the same lease agreement herein, is fundamentally part of the consideration in the contract and is not different from any other provision of the lease carrying an undertaking on the part of the lessor to act conditioned on the performance by the lessee. x x x The right of renewal constitutes a part of the lessee’s interest in the land and forms a substantial and integral part of the agreement.

Life is unpredictable! Break clauses give both parties an opportunity to terminate or reconsider the lease prior to the end of the contract.

In upholding the right of renewal in Philippine lease agreements, the Supreme Court adopted the very sensible view that:

[I]f we were to adopt the contrary theory that the terms and conditions to be embodied in the renewed contract were still subject to mutual agreement by and between the parties, then the option – which is an integral part of the consideration for the contract – would be rendered worthless. For then, the lessor could easily defeat the lessee’s right of renewal by simply imposing unreasonable and onerous conditions to prevent the parties from reaching an agreement, as in the case at the bar. As in a statute, no word, clause, sentence, provision or part of a contract shall be considered surplusage or superfluous, meaningless, void, insignificant or nugatory, if that can be reasonably avoided. To this end, a construction that will render every word operative is to be preferred over that which would make some words idle and nugatory.[i]

In fact, it makes sense for landlords and tenants to discuss with each other what would be the next steps for both of them.

Therefore, as decided in these cases, the right of renewal in Philippine lease agreements which gives the lessee the right and choice to renew the agreement for another 25 years is valid and binding on the parties.

0 Comments